It might seem just a touch difficult to defend Bluebeard. After all, if Charles Perrault is to be trusted—and we do trust him completely on the subject of talking cats—Bluebeard not only murdered several previous wives, but stored their corpses in a most unsanitary fashion.

And yet, some have noticed, shall we say, a touch of inconsistency in Perrault’s record, a few discrepancies that cannot be explained. Others, apparently, love the idea of a guy who is unafraid to have some bold color on his face. And so, Bluebeard has gained his defenders over the years—including one winner of the Noble Prize for Literature, Anatole France.

Born Jacques Anatole Thibault in 1844, Anatole France spent his early life buried in books. His father owned a bookshop that specialized in books about the French Revolution; young Jacques spent time both there and in various used book stalls, reading as he went. He was later sent to a religious school, which temporarily turned him against religion, or at least skeptical of it—although he would later explore the roots of Christianity and its connection with paganism in his novels. At the school, he started to write a few poems, publishing the first in 1869.

His bookstore experience later helped him earn a position in 1876 as a librarian for the French Senate, a position that both kept him buried in books—his preferred status—and allowed him time to write. A year later, he married the well-off Valerie Guerin, and with her money bought a house that allowed the couple to do plenty of entertaining in their salon—in an echo of the salon writers who had helped to develop the literary fairy tale in France just a couple hundred years earlier.

His first novel was published shortly afterwards, though it took him another two years to achieve critical and (some) financial success with his 1881 novel Le Crime de Sylvestre Bonnard. After that, his novel output remained steady, even as he continued to dabble in other literary forms—poetry, essays, letters, plays, literary criticism, and one serious biography. As he aged, he began turning away from his early crime novels towards works that explored history and myth, including a novel about one of the Three Wise Men, Balthazar, and fairy tales. He also socialized with members of the Decadent movement, while never quite joining it.

France also pursued relationships with multiple women who were not his wife, which eventually led to a divorce in 1893 and a long term yet somewhat open relationship with Madame Arman de Caillavat, a well to do married Jewish woman who hosted regular intellectual and literary gatherings, who has been credited with inspiring some of his later novels. His former wife kept custody of their daughter, leading to a later break between father and daughter; de Caillavat, meanwhile, encouraged France to write more. The multiple affairs and his divorce may have increased his sympathy for the figure of Bluebeard.

France had presumably encountered Charles Perrault’s tale at a relatively young age, but it was not until 1903, when he was nearly 60, that he felt the need to correct—or enhance—the record on Bluebeard, in The Seven Wives of Bluebeard. Based, France assures us, on “authentic documents,” the tale purports to tell the true history of Bluebeard, beginning by dismissing some of the more questionable, folkloric interpretations, as well as an earlier attempt to connect Bluebeard to a real historic figure, arguing that Bluebeard was, far from a serial killer, a gentle, misunderstood, unfortunate man. He also takes a moment to ding Shakespeare on his accuracy. Look, France, I’m sure you’re right about Macbeth, but a play where Macbeth and Lady Macbeth never murdered anyone and instead just talked about the difficulties of carpet cleaning in the days before steam cleaners and industrial products would not be nearly as interesting.

Anyway. France sets his tale in a very particular time period: 1650 (about when Perrault was writing his fairy tales), the age of Louis XIV and Versailles. Bernard de Montragoux is a nobleman who chooses to live in the country. Already, this signals a problem: Louis XIV built Versailles in part to ensure that his nobles could and would live in Versailles, not the country. The tale further assures us that de Montragoux willingly led a very simple life—a rather odd thing for an author who grew up surrounded by books about the French Revolution to say. Also, France explains, Bluebeard’s true problem with women was not his blue beard, or that whole murder thing, but the fact that he was shy.

Despite that shyness, Bluebeard manages to marry six women in rather quick succession. All have distinct names and personalities. One wife is an alcoholic; another wants to become the mistress of Louis XIV (to be fair, many of her contemporaries felt the same); one is extremely unfaithful—and eventually killed by a lover, not Bluebeard; one is easily tricked; and one devoted to celibacy. My favorite wife is probably the one who abandoned Bluebeard for the company of a dancing bear, because, bear. The recitation becomes a succinct list of all of the various things that can go wrong with a marriage: dissimilar interests, money problems, intellectual disparities, infidelity, and, well, bears.

And then the last wife appears, with her sister, Anne.

France presents The Seven Wives of Bluebeard less as a story, and more as a combination of history and historiography, while simultaneously introducing elements intended to make readers question the history. Bluebeard’s first six wives, for instance, are all very unlikely choices for a French nobleman in the Louis XIV period: nearly all come from the lower classes, and were not, prior to their marriages, “ladies of quality,” as France puts it. French aristocrats certainly slept around outside their social classes, but marrying outside their social classes was a much rarer event. And yet, within the story, no one seems to regard any of these marriages as a shocking mésalliance; indeed, a few of them are even suggested to Bluebeard as possible brides. To be fair, France was playing off a tale written by a man who had also detailed the career of that great social climber, Cinderella, which helps keep these marriages from feeling too unlikely.

Still a problem, though: all but one marriage is presumably bigamous. Certainly, some of the wives die, but not all of them do, and France is careful to note that Bluebeard obtained only one (expensive) annulment, putting not just the other marriages in grave legal doubt. As a defense against the allegation that Bluebeard murdered all six wives, it’s great; as an argument for Bluebeard’s greatness as a husband, it kinda fails, since I can’t help thinking that HEY, ONE OF MY WIVES IS STILL ALIVE SHE JUST RAN OFF WITH A BEAR is kinda one of those things that should be disclosed before the marriage proposal. Call me old fashioned if you like.

It’s also rather difficult not to notice that all six of these wives are deeply unhappy or unsatisfied for one reason or another. For all of the narrator’s attempts to argue that Bluebeard is a deeply sympathetic figure, the victim of his wives and his own kindly temperament, maligned by history and Charles Perrault, the narrative itself undermines this argument with a steady list of Bluebeard’s failures to make seven separate women happy. And although the narrator does not dwell on this point, his assurance that Bluebeard rejected several advantageous alliances before engaging on a series of disastrous unequal marriages rather makes me side-eye Bluebeard: did he reject these aristocratic marriages out of shyness, as the narrator argues, or because these were women he could not control—as the original tale by Perrault and some later comments by the narrator suggest?

Thus, The Seven Wives of Bluebeard becomes not just a look at the realities behind even the harshest of fairy tales, or a call for all us to question these tales, but a skeptical look at any attempt to justify or excuse the villains of history. On its surface a plea for a new interpretation of Bluebeard, and a defense of his character, it instead becomes a call to question, not so much history, but its tellers, and their interpretations of events.

Anatole France wrote other fairy tales, including a story about two of the courtiers in Sleeping Beauty’s palace and an original fairy tale called Bee: The Princess of the Dwarfs, which we may be looking at later. He married a second time in 1920, not to his long term mistress Madame Arman de Caillavat, but to Emma Laprevotte. The following year, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature for his contributions to French art and letters. He died in 1924.

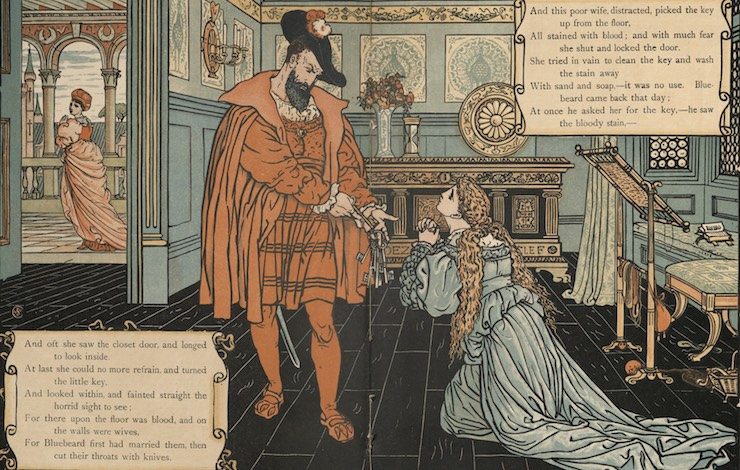

Top image from The Bluebeard Picture Book, London: George Routledge and Sons, 1875.

Mari Ness lives in central Florida.